The Persistence of God

“ ‘When I suggest that God’s love, patience, and persistence never end, many become angry.’

One Woman said, ‘I worked hard to live a good life, and now you tell me everyone is going to get in.’ ”

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard or read this response to the idea of Universal Reconciliation, God’s infinite grace for all. It, to me, says a lot about the person. Just exactly why is he a follower of “the way”. What is his “raison d’etre”. Like the authors, I have little sympathy for such a response. But, you know, when I think about it, I was exactly where she is. I was “works” oriented for 59 years, even though I claimed to have been “saved by grace through faith”.

I can really appreciate the parable of the workers in the vineyard, which the authors used in Chapter 6, which Jesus is said to have related. It is a perfect example of the above response. It is truly not our concern how our Source responds to people. Personally, my concern should be how I respond to him/her/it, and my response should be one of joy when I see “good” things happen to others. Why are some bothered by extravagant grace? I don’t know. I should know. I’ve been there.

I want you to know that I am not in agreement with the authors on everything in this chapter or in this book. The disagreements are not large, and may be nothing more than semantics, but I’m not totally sure that’s the case. When the authors discuss who will be the last to “come around”, who will be the last to end his rebellion against God, I’m not so sure any of us have a clue when this will take place, if at all. Will it be before the person dies, or will it be the moment they “cross over”. I will ready admit I don’t know the answer to that question. I will say at this point that I don’t see the purpose or reason for God causing the suffering, no matter how short, of a person for finite “sins” committed during our stay here on this plane. It does not appear to me to have any remedial or reformative value. Our problem seems to be our obsession with TIME. We feel it is invaluable to us. Yet, God knows no time, is not limited, or restricted by time. He could “purify” us in an instant (to use a time-characterized example). The authors seem to feel there is a possibility of a remedial state after death. But, that God’s grace will outlast even his most rebellious child.

Impatience is one of our big problems in today’s world. We don’t want to wait for any reason. I hate queues (lines). I detest having to stand in a line waiting. I’m impatient. “Fast food isn’t fast enough”. All of us identify with our fast-paced world we live in everyday. It’s a part of being human. The writers took considerable time to contrast our impatience with God’s infinite patience. They said, “The unlimited patience of God is the hope of the world.” Infinite patience is beyond our understanding. Yet, the picture of God presented in the Old Testament is often of a God of something less than infinite patience. This very enigma, the God of limited patience in the Old Testament, versus the God of unlimited patience in the New Testament, bothers me today. My “new” perception of the stories in the Bible, to which these authors contributed, has given me pause to consider the idea of “weighing” verses found in the OT especially. The character of God that is established by this book is one that I particularly like; a God of unlimited grace, patience, and persistence, not the impatient God often pictured in the Old Testament.

Why persistent grace? The authors say that the purpose of his persistence and patience is our “salvation”, a really loaded word in the English (religious) sense. I think I might have put it differently because of my own feelings about the word “salvation”. I think I might have used the word “reconciliation”. Salvation, is a multi-faceted word in religion today, and has become a “hot” topic even among those who believe in God’s infinite grace. I particularly like the two verses used in the chapter to describe God’s persistence; “He will NEVER leave nor forsake you” (Deuteronomy 31:6) and “Surely I will be with you ALWAYS, even unto the end of the age.” (Matthew 28:19-20) This last verse is a part of a somewhat controversial section at the end of Matthew’s gospel which many believe was added much later.

These verses plainly exhibit a God of infinite persistence. He’s not giving up on anyone. NEVER & ALWAYS are the words of a persistent God. The New Testament is replete with symbolic language that expresses that God is not interested in just a few chosen people, but wants and desires reconciliation with ALL. Time and again God states he wants ALL of us. Jesus is quoted to have said that he would draw (greek= drag) all men to himself. Sounds to me like a lot of persistence is involved in universal reconciliation.

If Grace is True, then the triumph of grace (God’s infinite persistence to reconcile ALL) is still not complete, and it won’t be until all are reconciled to God. When that will take place I do not know. I do know in my heart it WILL take place and it WILL be for everyone!

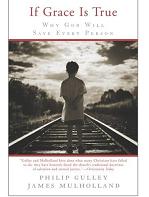

Chapter 5, titled “The Salvation of God” starts “I believe God will save every person”. It is, in essence, about Atonement, or how salvation is affected. And McGulley as an interesting view, at odds with mainstream thought.

Chapter 5, titled “The Salvation of God” starts “I believe God will save every person”. It is, in essence, about Atonement, or how salvation is affected. And McGulley as an interesting view, at odds with mainstream thought. If Grace Is True: Why God Will Save Every Person

If Grace Is True: Why God Will Save Every Person  This blog is aimed at discussing issues of “Inclusion”, by which we mean a wide variety of things. It is our theology, our philosophy, our deeply held myths, our emotional makeup and our experience that will determine just how inclusive or exclusive we are. All of us “draw a line” somewhere, implying excluding something, some people, some behavior, the question is, where? Why exclude anything or anyone. Or perhaps, why include them?

This blog is aimed at discussing issues of “Inclusion”, by which we mean a wide variety of things. It is our theology, our philosophy, our deeply held myths, our emotional makeup and our experience that will determine just how inclusive or exclusive we are. All of us “draw a line” somewhere, implying excluding something, some people, some behavior, the question is, where? Why exclude anything or anyone. Or perhaps, why include them?